Ornamentation is an interesting word. I say this because after the

lecture last week, it is hard for me to continue to define it through the other

terms that it is usually associated with- decorative, value addition,

accessorize and so on.

When asked to trace back our earliest mental images of garments, I

thought of the ancient roman and Greek gods, in their freely draped attire. So

is it safe to say, then, that anything above this simplistic form is

ornamentation? Or can the singular broaches they wore to gather the drapes at a

point also be considered ornamentation? I found myself exploring these answers

through this class.

ADOLF LOOS

I’ve had very little understanding of the history and origins of

textiles before this, which is part of why I never really understood how cloth

could be a medium to represent the socio-economic condition of a time or place.

This is why the documentary on Yinka Shonibare’s work had be surprised. He has

beautifully juxtaposed a representation of one culture with form and structure

from another. The irony in each of his pieces, particularly in the ‘ Scramble

for Africa’, is rather overwhelming. Firstly, on a visual front, you see the

serious postures and emphasis through hand gestures contrasted with the bright

and colorful batik fabric. It also seems to be a sardonic note on the fact that

there was no actual representation of the community being discussed at the

table that decided its future. The play on freedom and structure is apparent in

all of Shonibare’s work.

SCRAMBLE FOR AFRICA

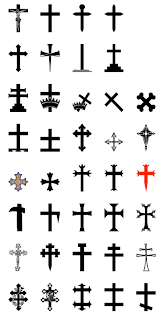

The lecture took an interesting turn when we began the discussions on

patterns and motifs, and how symbols, though remembered through their most

famous associations, may have entirely different origins. The best example of

this is the cross. Though everyone associates it with Christ and the crucifix,

we’re largely unaware of its Pagan origins. According to Vine’s

Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words, the shape of the

cross “had its origin in ancient Chaldea, and was used as the symbol of the god

Tammuz (being in the shape of the mystic Tau, the initial of his name) in that

country and in adjacent lands, including Egypt. Infact, the pagans were largely

received into the churches to retain their signs and symbols.

Through this class, I’ve had the opportunity to read into terms

that we hear so often. Concepts such as representation and abstraction, as well

as movements such as the Art and Crafts movement, led largely by a very

influential designer by the name of William Morris, who was best known for his

pattern making. Morris felt that the ‘diligent study of Nature’ was important,

as nature was the best example of God’s design. In 1981, Morris founded the

Kelmscott Press, names after the village near Oxford where he had lived since

1871. The Kelmscott Press produced high quality hand- printed books to be

cherished as objects d’art.

WILLIAM MORRIS

I’ll end along the same lines that the class began – fabric,

though looked upon primarily to cover and protect, serves as a channel for

understanding, communicating, teaching and of course, judging. We make a number

of assumptions through cloth on a daily basis.

Thus, by reading cloth, and the many threads linked to it, we can make

better sense of our social, political and even economic environment today.

No comments:

Post a Comment