Balotra is a small market town in the Barmer

District of Rajasthan state in India. It is about 100 km from Jodhpur.

It’s close to the river Luni, which had dried up 50 years ago.

Balotra is known for its traditional hand block printed textiles done with

wooden blocks and dyed with soft shades of Indigo, yellow and red onto hard

weaving cotton.

As

early as the 11th century AD, Indian women used to dress in what we

see today as the traditional Rajasthani style. The typical garments worn by the

women from Balotra comprises of a ghaggra skirt, choli bodice, and Odhani head

cloth. This simple and comfortable attire allows for easy movement during the

working day. The colour and motifs on the ghaggra differ for each community.

The agricultural women wear a skirt that is dark green to conceal the dirt from their daily work on the field. Their Odhani is however contrastingly bright and patterned.

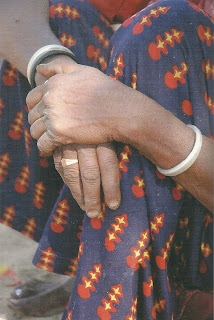

Married

women wear printed ghaggras that have a red border with yellow piping. The

minute the women becomes a widow, the Red border is removed from the skirt. In

addition, patterns and colours also change with the age of the women. As you

grow older, the colours of the attire become duller and the patterns become

simpler. The thickness of the cloth worn also determines economic status. The

women belonging to communities from a lower status wear coarser cotton cloth,

while those belonging to elite classes wear finer and lighter cotton.

.jpg) |

| Married women have red border at the hem which is removed when the women becomes a widow. |

.jpg) |

| Rabari family dress traditions- widow in cotton kuttaar print ghaggra and wax odhani (left), her daughter and grand daughter in identical synthetic kuttaar prints (2nd and 4th from left) and the unmarried youngest daughter in synthetic non traditional print. |

Textiles

play a major role in the culture of the Balotra communities. A woman would

receive from her husband a new set of clothes for every life changing event she goes through.Her marriages, pregnancy, birth of her first child, marriage of her

oldest son are some examples of the major events and the patterns on each

garment symbolizes are different for each occasion.

These

textiles worn by the local community groups contribute to the construction of

identity and visually differentiate each group from one another.The textiles

are often loaded with social meaning and can reveal the wearers position in

society, status, occupation, ethnic and religious relations, gender and marital

status. Different tribes and castes such as the Rabari’s, Chaudhury’s etc.

living in Balotra have their own dialects and social codes. In addition they

also have their own symbols and visual images, which are reflected through

their textiles.

The

designs on the textiles encompass nearly 20 plant and animal, and object

motifs, which are drawn from everyday surroundings and objects. Some of the

motifs include:

Phooli:

This motif shows intertwining flowers and is worn by the Maali community known

to be the legendary makers of temple flower garlands. The Maali community of

gardeners dominates a large proportion of the Balotra prints. Since their

occupation involves the growing of fruit, flowers and vegetables, the textiles

worn by them usually have prints of vegetation.

Gainda:

Worn by the middle aged Maali women depicts the marigold flowers (the most

widely cultivated flower crop in India used for medicinal, dyeing, religious,

flavoring and ornamental purposes).

Chameli:

This print depicts the sweet smelling Jasmine flowers. As they are sacred to Lord

Vishnu and used in garlands offered to temples, the Chameli motif is only worn

by Maali widows (women who have spent their lives hand cultivating these

delicate blossoms).

Mato

Ro Fatiya: A simple and subdued design only worn by widows and construction

workers who prepare foundations for village huts. The name is derived from the Sanskrit

word Mato, which means sand.

Goonda:

Is a striped design with intertwining plant motifs with small cherry like

fruit, that is worn by married women from the Chaudhury and Jhaat communities.

Women from these communities don’t work on the field. Instead Goonda a popular

berry used for making chutneys reflects their home-making skills.

Laung:

Traditional for all tribes and yet not to be worn by widows, this design

depicts the dried, unopened flower buds of cloves. Cloves are said to be

auspicious at the time of weddings and also have many medicinal uses.

Trifuli:

Is a three-flower motif. It’s the only design worn by young girls prior to

marriage. The flower on the print is stated to be daffodils- the delicate,

sweetly scented, yet short-lived spring flower. The daffodil is said to express bright, yet fleeting beauty of youth.

The

Process:

Dyeing:

- Washing-

The heavy cotton cloth is soaked for a week in a tank of plain water.

It is

then beaten and rinsed and ensured that all the impurities have been removed.

- Harda-

The washed cloth is treated with Harda (a thick, yellow paste made from the fruit

of the Myrobalan tree). The cloth is plunged into the Harda paste, trampled,

rung out and spread out to dry.

Printing:

- Coloured

pastes are applied using carved wooden blocks. First Syahi is applied (a

fermented mixture of horse shoe and molasses) Next, black outlines of Rekh is

applied, followed by Begar (another paste).

- The

cloth is dried in the sun and thoroughly washed and beaten.

Red

Dyeing:

- A

copper pot containing the red dye is heated over the fire.

- The

cloth is added while the dye is heated in the pot and stirred.

- On

removal from the dye bath, the Begar becomes red and the Syahi becomes black.

- The

cloth is again washed and beaten.

Dabu:

Returning

to the Printing table, the design is printed with Dabu resist (a smooth paste of soaked black earth, tree gum and wheat grains). This paste

is applied as a mask to the dyed areas.

Indigo:

- The

Dabu printed cloth is immersed in a vat of indigo dye.

- The

mixture is made from indigo, water and Lime powder.

- Earlier,

natural indigo was produced from the indigo plant. Now a synthetic one is used.

Yellow

and Greens:

For

designs that require yellow and green colour-

Dark

yellow is made from turmeric root and boiled Pomegranate rind. This yellow dye

can be used to over dye the indigo blue, to give a green shade.

Finishing:

Once

the printing and dyeing is finished, the cloth is again washed and beaten. This

strengthens the colours of the cloth.

Originally,

over 150 years ago, the Balotra designs were only printed in Shades of reds and

yellows. The red dye plants native to India- Majeeta and Al were used to create

a range of oranges, reds, purples and browns. The absence of blues and greens

in the local print may have been due to irregular supply of raw dye materials.

The travelling merchants and the movement of tribes such as Banjara and Rabari

brought supplies from out of state. The supply of Indigo was brought from the

south and west, where it was cultivated.

Changing

Traditions:

Until

recent Decades, Balotra hosted a thriving small-scale textile industry. A

number of family run print and dye businesses existed on the border of the

market town, working to provide cloth for the local community needs. The

printers would provide cloth to the local traders as well a community specific

stock, which they would carry from village to village during festival seasons.

Until the 20th century, the craftsmen would exchange their stock for

local produce and pay taxes to the local head in the form of their finest work.

Over

the past 30 years, this thriving textile activity has diminished, with local

printing families turning to other forms of income. Presently only a hand full of

hand block printers remain who contribute to produce the authentic ghaggra

prints by traditional methods for local use.

Source: Balotra-The Complex Language of Print, Anokhi Museum of Hand printing, Emma Ronald &David Dunning, AMHP Publications, 2007

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)